About Me

Daniel Ferrante completed his Ph.D. in theoretical physics at Brown University, winning the Physics Department’s awards for Scholarship and for excellence in Teaching. During his career in academia, he worked on a wide variety of numerical and computational methods, including complex/imaginary Monte Carlo, chaotic dynamical systems, multi-fractal systems, and stochastic differential equations. During this time, Ferrante was also responsible for the implementation and oversight for high performance computing infrastructure and other distributed computing systems, from commission and hardware installation to security and system administration.

Prior to SFL, Ferrante was a Sloan-Swartz Fellow, and later a Data Science Manager, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, modeling and analyzing big data in neuroscience. His work included data warehousing, data engineering, and quantitative big image analysis (60000×55000 pixels @ 0.5μm/pixel resolution) to study brain-wide connectivity in large >1.5PB datasets. Applications included disease modeling, segmentation, and cell-detection in various animal species as well as Topological Data Analysis to identify autism in the SFARI dataset for the Simons Foundation, and modeling the statistical evolution of brain regions. His experience with quantitative big image analysis serves as a backbone for work in the healthcare space, especially digital histopathology and the medical imaging space.

Ferrante is an expert in applied and computational methods, machine vision, and analytical modeling of complex systems. His recent projects include developing a state-of-the-art computer vision framework to classify and segment several objects within high-resolution satellite images; the detection framework can be applied to a host of infrastructure and development questions and provide insights on a national or global scale.

Miscellaneous projects include predicting cybersecurity vulnerabilities, an AI chatterbot platform with a built-in recommendation system, and 3D modeling of houses using photographs.

Physics

I work with mathematical and nonperturbative aspects of Gauge Theory, and their relations to symmetry breaking (local or global) and how the moduli space and its topology determine the quantization of the physical system at hand. I am also interested in quantum phases and the space of quantum field theories, non-linear Fredholm theory, branes and topological quantization (which is related to the previous topic via Index Theorems); noncommutative and spectral geometry, and their relation to deformation and geometric quantization; Higgs Bundles; Geometric Langlands Duality (dualities in general: AdS/CFT, modular and mirror symmetry, etc); quantum fields in curved spaces; higher gauge theory and category theory; and so on — and their relations to Quantum Gravity.

Using the arXivs’ notation: hep-th, math-ph, hep-lat, gr-qc.

My scientific articles can be found in the arXivs, or in inSPIRE; and my Lattes CV (pt_BR).

Solution Space of Gauge Theories and Quantum Phases

Quantum Phases are defined to be the different quantum states at zero temperature. A Quantum Phase Transition (QPT) happens when a system undergoes a change from one quantum phase to another, at zero temperature. It describes an abrupt change in the ground-state of the system caused by its quantum fluctuations. A Quantum Critical Point (QCP) is a point in the phase diagram of a system (at zero temperature) that separates two quantum phases. In addition to this, QCPs distort the fabric of the phase diagram creating a phase of “quantum critical matter” fanning out to finite temperatures from the QCP. As expected, at the QCP, the system exhibits spacetime scale invariance, justifying the idea that it can be modeled via a Conformal Field Theory (CFT) — because of this, sometimes the QCP is referred only as a “conformal point”. The connection with High Energy Physics, namely with Gauge Theory, can be made almost instantly. There are two ways to best understand this phenomenon. One of them is via the analytic continuation of the partition function of a given system. However, this can be particularly tricky, since it involves ℂomplex (Picard–Lefschetz) and infinite-dimensional Morse theory. On the other hand, this scenario can be addressed in a constructive manner, that reveals more clearly what is at stake. If we start from a 0-dimensional gauge theory (D0-brane), for any field (scalar, fermion, vector, matrix, tensor, Lie or graded Lie algebra), and evaluate its Schwinger–Dyson equation (which is nothing but the differential version of the integral problem treated via a partition function), we clearly see that, because this differential equation has as many solutions as its degree, we are supposed to have one integral representation for each one of these solutions — and each one of these integral representations is what we call a partition function. Therefore, there will be more than one possible partition function, one for each available quantum phase. And the relation among them can be clearly seen through appropriate analytic continuations and asymptotic analysis (Stokes’ phenomena, wall-crossing), which is how this approach ties in with the previously mentioned one. This maps out the Solution Space of a given Gauge Theory, revealing its “glassy” character, somewhat analogous to what happens in spin systems. Furthermore, understanding the Feynman Path Integral as a Linear Canonical Transform, we can make an analogy with the Penrose–Ward transform, establishing a correspondence between two spaces, where one contains the appropriate integration cycles, while the other contains a certain choice of [vector] parameters for a representation of the system’s singularities in terms of Fox’s H-function (which is a Mellin–Barnes transform, usually of a more general character than a polylogarithm). Also, with this understanding, we are also able to generalize the interpretation of Feynman’s Path Integral as a sum of more general paths than just a Brownian one, such as Lévy flights, and so on. This brings to the foreground the nonlinear Fredholm theory of the Schwinger–Dyson differential operator, which in turn has something to say about the construction of Seiberg–Witten invariants. Finally, understanding the role of the matrix parameter of the Linear Canonical Transform helps to clarify the origin of some dualities.

My research interests include:

- Quantum Gauge Theory: Symmetry Breaking (spontaneous or otherwise), Solution Space of QFTs and Quantum Phases, Moduli Spaces, Non-Linear Fredholm Theory, Vacuum Stability and Spontaneous Decay, Novel Numerical Methods (discrete differential forms, geometric discretization);

- Quantum Gravity: Brane Quantization, ℂomplex and Generalized Partition Functions, Topology Change, Twistor methods, Topological Field Theories, String Field Theory, Dualities, Noncommutative and Spectral Geometry, Category Theory.

Interesting Links

- Physics.SE;

- Theoretical Physics FAQ;

- The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences;

- Theoretical Mathematics;

- Duhem-Quine Thesis;

- The History of the Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble development of the Theory of Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Gauge Particles, by G. Guralnik.

Neuroscience

Lately, I have also been peaking at some problems in Theoretical and Computational Neuroscience, e.g., Ersätz-Brain. In modern parlance, this is also known as Capsule Networks.

Original About Text

This is the front page of a website that is powered by the academicpages template and hosted on GitHub pages. GitHub pages is a free service in which websites are built and hosted from code and data stored in a GitHub repository, automatically updating when a new commit is made to the respository. This template was forked from the Minimal Mistakes Jekyll Theme created by Michael Rose, and then extended to support the kinds of content that academics have: publications, talks, teaching, a portfolio, blog posts, and a dynamically-generated CV. You can fork this repository right now, modify the configuration and markdown files, add your own PDFs and other content, and have your own site for free, with no ads! An older version of this template powers my own personal website at stuartgeiger.com, which uses this Github repository.

A data-driven personal website

Like many other Jekyll-based GitHub Pages templates, academicpages makes you separate the website’s content from its form. The content & metadata of your website are in structured markdown files, while various other files constitute the theme, specifying how to transform that content & metadata into HTML pages. You keep these various markdown (.md), YAML (.yml), HTML, and CSS files in a public GitHub repository. Each time you commit and push an update to the repository, the GitHub pages service creates static HTML pages based on these files, which are hosted on GitHub’s servers free of charge.

Many of the features of dynamic content management systems (like Wordpress) can be achieved in this fashion, using a fraction of the computational resources and with far less vulnerability to hacking and DDoSing. You can also modify the theme to your heart’s content without touching the content of your site. If you get to a point where you’ve broken something in Jekyll/HTML/CSS beyond repair, your markdown files describing your talks, publications, etc. are safe. You can rollback the changes or even delete the repository and start over – just be sure to save the markdown files! Finally, you can also write scripts that process the structured data on the site, such as this one that analyzes metadata in pages about talks to display a map of every location you’ve given a talk.

Getting started

- Register a GitHub account if you don’t have one and confirm your e-mail (required!)

- Fork this repository by clicking the “fork” button in the top right.

- Go to the repository’s settings (rightmost item in the tabs that start with “Code”, should be below “Unwatch”). Rename the repository “[your GitHub username].github.io”, which will also be your website’s URL.

- Set site-wide configuration and create content & metadata (see below – also see this set of diffs showing what files were changed to set up an example site for a user with the username “getorg-testacct”)

- Upload any files (like PDFs, .zip files, etc.) to the files/ directory. They will appear at https://[your GitHub username].github.io/files/example.pdf.

- Check status by going to the repository settings, in the “GitHub pages” section

MathJax Examples

Paragraph ipsum lorem…

Another one…

And, another one…

Site-wide configuration

The main configuration file for the site is in the base directory in _config.yml, which defines the content in the sidebars and other site-wide features. You will need to replace the default variables with ones about yourself and your site’s github repository. The configuration file for the top menu is in _data/navigation.yml. For example, if you don’t have a portfolio or blog posts, you can remove those items from that navigation.yml file to remove them from the header.

Create content & metadata

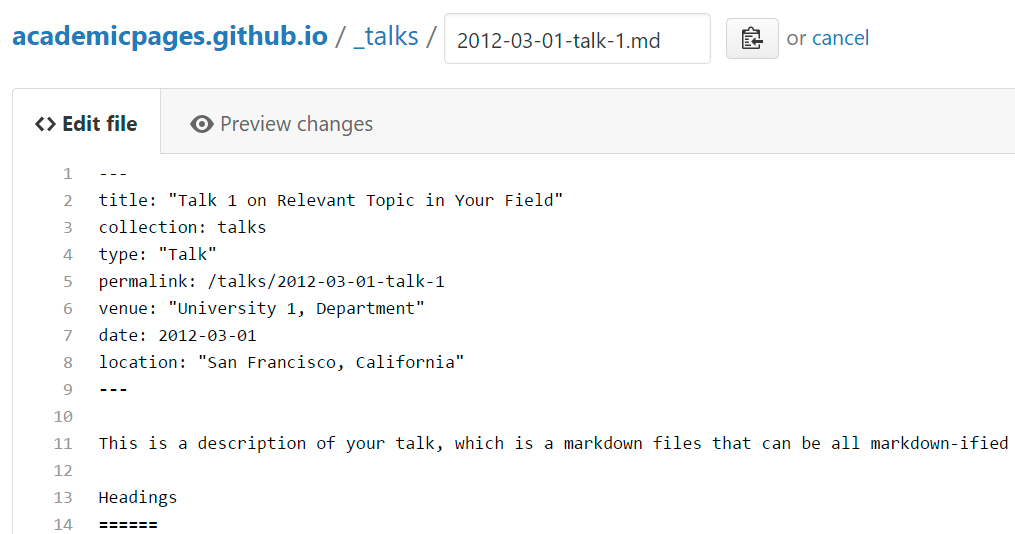

For site content, there is one markdown file for each type of content, which are stored in directories like _publications, _talks, _posts, _teaching, or _pages. For example, each talk is a markdown file in the _talks directory. At the top of each markdown file is structured data in YAML about the talk, which the theme will parse to do lots of cool stuff. The same structured data about a talk is used to generate the list of talks on the Talks page, each individual page for specific talks, the talks section for the CV page, and the map of places you’ve given a talk (if you run this python file or Jupyter notebook, which creates the HTML for the map based on the contents of the _talks directory).

Markdown generator

I have also created a set of Jupyter notebooks that converts a CSV containing structured data about talks or presentations into individual markdown files that will be properly formatted for the academicpages template. The sample CSVs in that directory are the ones I used to create my own personal website at stuartgeiger.com. My usual workflow is that I keep a spreadsheet of my publications and talks, then run the code in these notebooks to generate the markdown files, then commit and push them to the GitHub repository.

How to edit your site’s GitHub repository

Many people use a git client to create files on their local computer and then push them to GitHub’s servers. If you are not familiar with git, you can directly edit these configuration and markdown files directly in the github.com interface. Navigate to a file (like this one and click the pencil icon in the top right of the content preview (to the right of the “Raw | Blame | History” buttons). You can delete a file by clicking the trashcan icon to the right of the pencil icon. You can also create new files or upload files by navigating to a directory and clicking the “Create new file” or “Upload files” buttons.

Example: editing a markdown file for a talk

For more info

More info about configuring academicpages can be found in the guide. The guides for the Minimal Mistakes theme (which this theme was forked from) might also be helpful.